AEROPLANE JAN 2024 FAIRCHILD

C-119 FLYING BOX CAR C-82 PACKET BAC TSR.2 RAF COLD WAR STRIKE / RECONNAISSANCE

AIRCRAFT RNZAF NEW ZEALAND P-51 MUSTANG WW1 ITALIAN CAPRONI Ca3 WW2 GERMAN

LUFTWAFFE HEINKEL He177 GREIF BABY BLITZ AVRO TRANSPORT COMPANY RAF VICKERS

WELLINGTON TRAINING SWEDISH AIR FORCE SVENSA FLYGVAPENT GLOSTER GLADIATOR

BIPLANE FIGHTER WW2 AIR MAIL BY De HAVILLAND RAF GERMANY RAFG PHANTOMS

KEY PUBLISHING SOFTBOUND BOOK in ENGLISH

---------------------------------------

Additional Information from Internet Encyclopedia

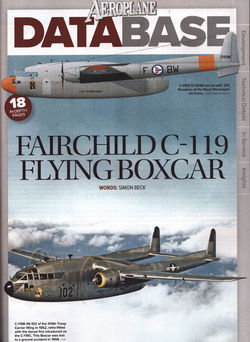

The Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcar (Navy and Marine Corps

designation R4Q) was an American military transport aircraft developed from the

World War II-era Fairchild C-82 Packet, designed to carry cargo, personnel,

litter patients, and mechanized equipment, and to drop cargo and troops by

parachute. The first C-119 made its initial flight in November 1947, and by the

time production ceased in 1955, more than 1,100 had been built.

Development

The Air Force C-119 and Navy R4Q was initially a redesign

of the earlier C-82 Packet, built between 1945 and 1948. The Packet had

provided limited service to the Air Force's Tactical Air Command and Military

Air Transport Service before its design was found to have several serious

problems. Though it continued in service till replaced, all of these were

addressed in the C-119, which had its first test flight already in 1947.

To improve pilot visibility, enlarge the cargo area, and

streamline aerodynamics, the C-119 cockpit was moved forward to fit flush with

the nose, rather than over the cargo compartment. The correspondingly longer

fuselage resulted in more usable cargo space and larger loads than the C-82

could accommodate. The C-119 also got new engines, with 60% more power,

four-bladed props to three, and a wider and stronger airframe. The first C-119

prototype (called the XC-82B) made its initial flight in November 1947, with

deliveries of C-119Bs from Fairchild's Hagerstown, Maryland factory beginning

in December 1949.

The AC-119G Shadow gunship variant was fitted with four

six-barrel 7.62 mm (0.300 in) NATO miniguns, armor plating, flare launchers,

and night-capable infrared equipment. Like the AC-130 that recently preceded

it, the AC-119 proved to be a potent weapon. The AC-119 was made more deadly by

the introduction of the AC-119K Stinger version, which featured the addition of

two General Electric M61 Vulcan 20 mm (0.79 in) cannon, improved avionics, and

two underwing-mounted General Electric J85-GE-17 turbojet engines, adding

nearly 6,000 lbf (27 kN) of thrust.

Other major variants included the EC-119J, used for

satellite tracking, and the YC-119H Skyvan prototype, with larger wings and

tail.

In civilian use, many C-119s feature the

"Jet-Pack" modification, which incorporates a 3,400 lbf (15,000 N)

Westinghouse J34 turbojet engine in a nacelle above the fuselage.

In December 1950, after People's Republic of China

Expeditionary People's Volunteer Army troops blew up a bridge [N 1]at a narrow

point on the evacuation route between Koto-ri and Hungnam, blocking the

withdrawal of U.N. forces, eight U.S. Air Force C-119 Flying Boxcars flown by

the 314th Troop Carrier Group [6][N 2] were used to drop portable bridge

sections by parachute. The bridge, consisting of eight separate sixteen-foot

long, 2,900-pound sections, was dropped one section at a time, using two parachutes

on each section. Four of these sections, together with additional wooden

extensions were successfully reassembled into a replacement bridge by Marine

Corps combat engineers and the US Army 58th Engineer Treadway Bridge Company,

enabling U.N. forces to reach Hungnam.

From 1951 to 1962, C-119C, F and G models served with

U.S. Air Forces in Europe (USAFE) and Far East Air Forces (FEAF) as the

first-line Combat Cargo units, and did yeoman work as freight haulers with the

60th Troop Carrier Wing, the 317th Troop Carrier Wing and the 465th Troop

Carrier Wing in Europe, based first in Germany and then in France with roughly

150 aircraft operating anywhere from Greenland to India. A similar number of

aircraft served in the Pacific and the Far East. In 1958, the 317th absorbed the

465th, and transitioned to the C-130s, but the units of the former 60th Troop

Carrier Wing, the 10th, 11th and 12th Troop Carrier Squadrons, continued to fly

C-119s until 1962, the last non-Air Force Reserve and non-Air National Guard

operational units to fly the "Boxcars."

Perhaps the most remarkable use of the C-119 was the

aerial recovery of balloons, UAVs, and even satellites. The first use of this

technique was in 1955, when C-119s were used to recover Ryan AQM-34 Firebee

unmanned targets.[7] The 456th Troop Carrier Wing, which was attached to the

Strategic Air Command (SAC) from 25 April 1955 – 26 May 1956, used C-119s to

retrieve instrument packages from high-altitude reconnaissance balloons. C-119s

from the 6593rd Test Squadron based at Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii performed

several aerial recoveries of film-return capsules during the early years of the

Corona spy satellite program. On 19 August 1960, the recovery by a C-119 of

film from the Corona mission code-named Discoverer 14 was the first successful

recovery of film from an orbiting satellite and the first aerial recovery of an

object returning from Earth orbit.

The C-119 went on to see extensive service in French

Indochina, beginning in 1953 with aircraft secretly loaned by the CIA to French

forces for troop support. These aircraft were generally flown in French

markings by American CIA pilots often accompanied by French officers and

support staff. The C-119 was to play a major role during the siege at Dien Bien

Phu, where they flew into increasingly heavy fire while dropping supplies to

the besieged French forces.[9] The only two American pilot casualties of the siege

at Dien Bien Phu were James B. McGovern Jr. and Wallace A. Buford. Both pilots,

together with a French crew member, were killed in early June, 1954, when their

C-119, while making an artillery drop, was hit and crippled by Viet Minh

anti-aircraft fire; the aircraft then flew an additional 75 miles (121 km) into

Laos before it crashed.

During the Vietnam War, the incredible success of the

Douglas AC-47 Spooky continued, but limitations of the size and carrying

capacity of the plane led the USAF to develop a larger plane to carry more

surveillance gear, weaponry, and ammunition, the AC-130 Spectre. However, due

to the strong demands of C-130s for cargo use there were not enough Hercules

frames to provide Spectres for operations against the enemy. The USAF filled

the gap by converting C-119s into AC-119s each equipped with four 7.62 minigun

pods, a Xenon searchlight, night observation sight, flare launcher, fire

control computer and TRW fire control safety display to prevent incidents of

friendly fire. The new AC-119 squadron was given the call-sign

"Creep" that launched a wave of indignation that led the Air Force to

change the name to "Shadow" on 1 December 1968.[10] C-119Gs were

modified as AC-119G Shadows and AC-119K Stingers. They were used successfully

in both close air support missions in South Vietnam and interdiction missions

against trucks and supplies along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. All the AC-119G

Gunships were transferred to the Republic of Vietnam Air Force starting in 1970

as the American forces began to be withdrawn.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Air National Guard

and USAF Reserve pilots flew C-119's to drop parachutist students for the US

Army Parachute School at Ft. Benning, Georgia.

After retirement from USAF active duty, substantial

numbers of C-119s and R4Qs soldiered on in the U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps,

the Air Force Reserve and the Air National Guard until the mid-1970s, the R4Qs

also being redesignated as C-119s in 1962. The last military use of the C-119

by the United States ended in 1974 when a single squadron of Navy Reserve

C-119s based at Naval Air Facility Detroit/Selfridge Air National Guard Base

near Detroit, Michigan, and two squadrons based at Naval Air Station Los Alamitos,

California replaced their C-119s with newer aircraft.

Many C-119s were provided to other nations as part of the

Military Assistance Program, including Belgium, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Italy,

Jordan, Taiwan, and (as previously mentioned) South Vietnam. The type was also

used by the Royal Canadian Air Force, and by the United States Navy and United

States Marine Corps under the designation R4Q until 1962 when they were also

redesignated as C-119.

Variants

C-119B

Production variant with two P&W R-4360-30 engines, 55

built.

C-119F

Production variant, (71 produced by Henry Kaiser with

Wright R-3350 engines), 256 built for the USAF and RCAF.

C-119G

As C-119F with different propellers, 480 built, some

converted from Fairchild or Kaiser built C-119F.

AC-119G Shadow

C-119G modified as gunships, 26 conversions.

R4Q-1

United States Navy & United States Marine Corps

version of the C-119C, 39 built.

R4Q-2

United States Navy and United States Marine Corps version

of the C-119F, later re-designated C-119F, 58 built.

Operators

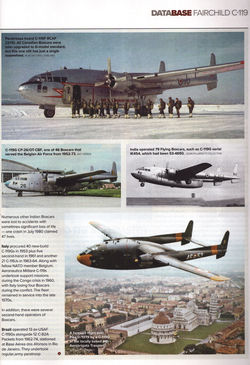

C-119 Flying Boxcars from the 403rd Troop Carrier Wing

Belgium

Belgian Air Force received 40 new aircraft using Mutual

Defense Air Program (MDAP) funds delivered from 1952, 18 x C-119F and 22

C-119Gs. Six surplus Kaiser-built USAF C-119G were acquired in 1960. All C-119F

were retired in 1955 shortly after the arrival of last C-119G, eight were sold

to Royal Norwegian Air Force after being rebuilt to C-119G specs by Sabena

technicians, the remaining ten were sent to Spain but proved unsuccessful and

were ultimately re-acquired by Belgian Air Force in 1960–1961, rebuilt as

C-119G.[12][13]

Brazil

Brazilian Air Force received 11 former USAF C-119Gs using

Military Aid Program funding in 1962. An additional USAF C-119G was acquired in

1962 as an attrition replacement.

Canada

Royal Canadian Air Force received 35 new C-119Fs

delivered from 1953, later upgraded to C-119G standard.

Taiwan

Republic of China Air Force received 114 former USAF

aircraft, they were in service from 1958 to 1997.

Ethiopia

Ethiopian Air Force received eight former USAF aircraft

using Military Aid Program funding, after modification to C-119K standard with

underwing auxiliary jets they were delivered in two batched, five in 1970 and

three in 1971. Two former Belgian Air Force C-119Gs were acquired in 1972 as

spares source.

France

French Air Force operated in Indochina nine aircraft

loaned from USAF.

India

Indian Air Force received 79 aircraft. Italy

Italian Air Force operated 40 C-119G new aircraft as

Mutual Defence Assistance Program, five C-119G former USAF and transferred to

United Nations in December 1960 and 25 C-119J surplus USAF / ANG aircraft.[14]

The last one flew in 1979.[15]

Jordan

Royal Jordanian Air Force received four former USAF

aircraft.

Morocco

Royal Moroccan Air Force received 12 former USAF aircraft

and six former Canadian aircraft.

Norway

Royal Norwegian Air Force received 8 surplus Belgian

aircraft.

Spain

Spanish Air Force received 10 former Belgian C-119F

delivered by USAF but rejected all.

South Vietnam

Republic of Vietnam Air Force received 91 aircraft

transferred from USAF.

United Nations

Five former USAF aircraft donated, operated by the Indian

Air Force then passed to the Italian Air Force. United States

---------------------------------------

The British Aircraft Corporation TSR-2 is a cancelled

Cold War strike and reconnaissance aircraft developed by the British Aircraft

Corporation (BAC), for the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the late 1950s and early

1960s. The TSR-2 was designed around both conventional and nuclear weapons

delivery: it was to penetrate well-defended frontline areas at low altitudes

and very high speeds, and then attack high-value targets in rear areas. Another

intended combat role was to provide high-altitude, high-speed stand-off,

side-looking radar and photographic imagery and signals intelligence, aerial

reconnaissance. Only one airframe flew and test flights and weight-rise during

design indicated that the aircraft would be unable to meet its original

stringent design specifications. The design specifications were reduced as the

result of flight testing.

The TSR-2 was the victim of ever-rising costs and

inter-service squabbling over Britain's future defence needs, which together

led to the controversial decision in 1965 to scrap the programme. It was

decided to order an adapted version of the General Dynamics F-111 instead, but

that decision was later rescinded as costs and development times increased. The

replacements included the Blackburn Buccaneer and McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom

II, both of which had previously been considered and rejected early in the

TSR-2 procurement process. Eventually, the smaller swing-wing Panavia Tornado

was developed and adopted by a European consortium to fulfil broadly similar

requirements to the TSR-2.

Development

The introduction of the first jet engines in the

late-World War II period led to calls for new jet-powered versions of

practically every aircraft then flying. Among these was the design of a

replacement for the de Havilland Mosquito, at that time among the world's

leading medium bombers. The Mosquito had been designed with the express intent

of reducing the weight of the aircraft in order to improve its speed as much as

possible. This process led to the removal of all defensive armament, improving

performance to the point where it was unnecessary anyway. This high-speed

approach was extremely successful, and a jet-powered version would be even more

difficult to intercept.

Mission

The envisioned "standard mission" for the TSR-2

was to carry a 2,000 lb (910 kg) weapon internally for a combat radius of 1,000

nautical miles (1,200 mi; 1,900 km). Of that mission 100 nautical miles (120

mi; 190 km) was to be flown at higher altitudes at Mach 1.7 and the 200 nmi

(230 mi; 370 km) into and out of the target area was to be flown as low as 200

ft at a speed of Mach 0.95. The remainder of the mission was to be flown at

Mach 0.92. If the entire mission were to be flown at the low 200 ft altitude,

the mission radius was reduced to 700 nmi (810 mi; 1,300 km). Heavier weapons

loads could be carried with further reductions in range.[3] Plans for

increasing the TSR-2's range included fitting external tanks: one

450-imperial-gallon (540 US gal; 2,000 L) tank under each wing or one 1,000 imp

gal (1,200 US gal; 4,500 L) tank carried centrally below the fuselage. If no

internal weapons were carried, a further 570 imp gal (680 US gal; 2,600 L)

could be carried in a tank in the weapons bay.[3] Later variants would have

been fitted with variable-geometry wings.

The TSR-2 was also to be equipped with a reconnaissance

pack in the weapons bay which included an optical linescan unit built by EMI,

three cameras and a sideways-looking radar (SLR) in order to carry out the

majority of its reconnaissance tasks. Unlike modern linescan units that use

infrared imaging, the TSR-2's linescan would use daylight imaging or an

artificial light source to illuminate the ground for night reconnaissance.

Tactical nuclear weapons

Carriage of the existing Red Beard tactical nuclear bomb

had been specified at the beginning of the TSR-2 project, but it was quickly

realised that Red Beard was unsuited to external carriage at supersonic speeds,

had safety and handling limitations, and its 15 kt yield was considered

inadequate for the targets assigned. Instead, in 1959, a successor to Red

Beard, an "Improved Kiloton Bomb" to a specification known as

Operational Requirement 1177 (OR.1177), was specified for the TSR-2. In the

tactical strike role, the TSR-2 was expected to attack targets beyond the

forward edge of the battlefield assigned to the RAF by NATO, during day or

night and in all weathers. These targets comprised missile sites, both hardened

and soft, aircraft on airfields, runways, airfield buildings, airfield fuel

installations and bomb stores, tank concentrations, ammunition and supply

dumps, railways and railway tunnels, and bridges. OR.1177 specified 50, 100,

200 and 300 kt yields, assuming a circular error probable of 1,200 ft (370 m)

and a damage probability of 0.8, and laydown delivery capability, with burst

heights for targets from 0 to 10,000 ft (3,000 m) above sea level. Other

requirements were a weight of up to 1,000 lb (450 kg), a length of up to 144 in

(3.7 m), and a diameter up to 28 in (710 mm) (the same as Red Beard).

Design

TSR-2 XR222 engine exhaust nozzles photographed at

Duxford, 2009. The hinged panel in the centre above the engine nozzles contains

the braking parachute

Throughout 1959, English Electric (EE) and Vickers worked

on combining the best of both designs in order to put forward a joint design

with a view to having an aircraft flying by 1963, while also working on merging

the companies under the umbrella of the British Aircraft Corporation. EE had

put forward a delta winged design and Vickers, a swept wing on a long fuselage.

The EE wing, born of their greater supersonic experience, was judged superior

to Vickers, while the Vickers fuselage was preferred. In effect, the aircraft

would be built 50/50: Vickers the front half, EE the rear.

The TSR-2 was to be powered by two Bristol-Siddeley

Olympus reheated turbojets, advanced variants of those used in the Avro Vulcan.

The Olympus would be further developed and would power the supersonic Concorde.

The design featured a small shoulder-mounted delta wing with down-turned tips,

an all-moving swept tailplane and a large all-moving fin. Blown flaps were

fitted across the entire trailing edge of the wing to achieve the short takeoff

and landing requirement, something that later designs would achieve with the

technically more complex swing-wing approach. No ailerons were fitted, control

in roll instead being implemented by differential movement of the slab

tailplanes. The wing loading was high for its time, enabling the aircraft to

fly at very high speed and low level with great stability without being

constantly upset by thermals and other ground-related weather phenomena. The EE

Chief Test Pilot, Wing Commander Roland Beamont, favourably compared the

TSR-2's supersonic flying characteristics to the Canberra's own subsonic flight

characteristics, stating that the Canberra was more troublesome.

According to the Flight Envelope diagram, TSR2 was

capable of sustained cruise at Mach 2.05 at altitudes between 37,000 ft (11,000

m) and 51,000 ft (16,000 m) and had a dash speed of Mach 2.35 (with a limiting

leading edge temperature of 140 °C).

The aircraft featured some extremely sophisticated

avionics for navigation and mission delivery, which would also prove to be one

of the reasons for the spiralling costs of the project. Some features, such as

forward looking radar (FLR) and side-looking radar for navigational fixing,

only became commonplace on military aircraft years later. These features

allowed for an innovative autopilot system which, in turn, enabled long

distance terrain-following sorties as crew workload and pilot input had been

greatly reduced.

There were considerable problems with realising the

design. Some contributing manufacturers were employed directly by the Ministry

rather than through BAC, leading to communication difficulties and further cost

overruns. Equipment, an area in which BAC had autonomy, would be supplied by

the Ministry from "associate contractors", although the equipment

would be designed and provided by BAC, subject to ministry approval. The

overall outlay of funds made it the largest aircraft project in Britain to

date.

Operational history

Testing

Serial number XR222 was one of only three "flight

ready" TSR-2s completed, photographed at the Supermarine Spitfire 60th

Anniversary Airshow, Duxford, 1996.

Despite the increasing costs the first two of the

development batch aircraft were completed. Engine development and undercarriage

problems led to delays for the first flight which meant that the TSR-2 missed

the opportunity to be displayed to the public at 1964's Farnborough Airshow. In

the days leading up to the testing, Denis Healey, the Opposition shadow

secretary for defence, had criticised the aircraft saying that by the time it

was introduced it would face "new anti-aircraft" missiles that would

shoot it down making it prohibitively expensive at £16 million per aircraft (on

the basis of only 30 ordered).

Test pilot Roland Beamont finally made the first flight

from the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) at

Boscombe Down, Wiltshire, on 27 September 1964. Initial flight tests were all

performed with the undercarriage down and engine power strictly controlled—with

limits of 250 kn (290 mph; 460 km/h) and 10,000 ft (3,000 m) on the first

(15-minute) flight. Shortly after takeoff on XR219's second flight, vibration

from a fuel pump at the resonant frequency of the human eyeball caused the

pilot to throttle back one engine to avoid momentary loss of vision.

Only on the 10th test flight was the landing gear

successfully retracted—problems preventing this on previous occasions, but

serious vibration problems on landing persisted throughout the flight testing

programme. The first supersonic test flight (Flight 14) was achieved on the

transfer from A&AEE, Boscombe Down, to BAC Warton. During the flight, the

aircraft achieved Mach 1 on dry power only (supercruise). Following this,

Beamont lit a single reheat unit as the other engine's reheat fuel pump was

unserviceable, with the result that the aircraft accelerated away from the

chase English Electric Lightning (a high speed interceptor) flown by Wing

Commander James "Jimmy" Dell, who had to catch up using reheat on

both engines. On flying the TSR-2 himself, Dell described the prototype as

handling "like a big Lightning".

Over a period of six months, a total of 24 test flights

were conducted. Most of the complex electronics were not fitted to the first

aircraft, so these flights were all concerned with the basic flying qualities

of the aircraft which, according to the test pilots involved, were outstanding.

Speeds of Mach 1.12 and sustained low-level flights down to 200 ft were

achieved above the Pennines. Undercarriage vibration problems continued,

however, and only in the final few flights, when XR219 was fitted with

additional tie-struts on the already complex landing gear, was there a

significant reduction in them. The last test flight took place on 31 March

1965.

Although the test flying programme was not completed and

the TSR-2 was undergoing typical design and systems modifications reflective of

its sophisticated configuration, "[T]here was no doubt that the airframe

would be capable of accomplishing the tasks set for it and that it represented

a major advance on any other type."

Costs continued to rise, which led to concerns at both

company and government upper management levels, and the aircraft was also

falling short of many of the requirements laid out in OR.343, such as takeoff

distance and combat radius. As a cost-saving measure, a reduced specification

was agreed upon, notably reductions in combat radius to 650 nmi (750 mi; 1,200

km), the top speed to Mach 1.75 and takeoff run up increased from 1,800 to

3,000 feet (550 to 915 m).

Project cancellation

XR220 at the RAF Museum, Cosford, 2007. The two cockpit

canopies are coated with a thin film of gold to protect the occupant's eyes

from a nuclear flash

By the 1960s, the United States military was developing

the swing-wing F-111 project as a follow-on to the Republic F-105 Thunderchief,

a fast low-level fighter-bomber designed in the 1950s with an internal bay for

a nuclear weapon. There had been some interest in the TSR-2 from Australia for

the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), but in 1963, the RAAF chose to buy the

F-111 instead, having been offered a better price and delivery schedule by the

American manufacturer. Nonetheless, the RAAF had to wait 10 years before the

F-111 was ready to enter service, by which time the anticipated programme cost

had tripled. The RAF was also asked to consider the F-111 as an alternative

cost-saving measure. In response to suggestions of cancellation, BAC employees

held a protest march, and the new Labour government, which had come to power in

1964, issued strong denials. However, at two Cabinet meetings held on 1 April

1965, it was decided to cancel the TSR-2 on the grounds of projected cost, and

instead to obtain an option agreement to acquire up to 110 F-111 aircraft with

no immediate commitment to buy. This decision was announced in the budget

speech of 6 April 1965. The maiden flight of the second development batch

aircraft, XR220, was due on the day of the announcement, but following an

accident in conveying the airframe to Boscombe Down, coupled with the

announcement of the project cancellation, it never happened. Ultimately, only

the first prototype, XR219, ever took to the air. A week later, the Chancellor

defended the decision in a debate in the House of Commons, saying that the

F-111 would prove cheaper.

All airframes were then ordered to be destroyed and

burned.

"The trouble with the TSR-2 was that it tried to

combine the most advanced state of every art in every field. The aircraft firms

and the RAF were trying to get the Government on the hook and understated the

cost. But TSR-2 cost far more than even their private estimates, and so I have

no doubt about the decision to cancel."

Denis Healey, then Minister of Defence.

Aeronautical engineer and designer of the Hawker

Hurricane Sir Sydney Camm said of the TSR-2: "All modern aircraft have

four dimensions: span, length, height and politics. TSR-2 simply got the first

three right."

TSR-2 replacements

To replace the TSR-2, the Air Ministry initially placed

an option for the F-111K (a modified F-111A with F-111C enhancements) but also

considered two other choices: a Rolls-Royce Spey (RB.168 Spey 25R) conversion

of a Dassault Mirage IV (the Dassault/BAC Spey-Mirage IV) and an enhanced

Blackburn Buccaneer S.2 with a new nav-attack system and reconnaissance

capability, referred to as the "Buccaneer 2-Double-Star". Neither

proposal was pursued as a TSR-2 replacement although a final decision was

reserved until the 1966 Defence Review. Defence Minister Healey's memo about

the F-111 and the Cabinet minutes regarding the final cancellation of the TSR-2

indicate that the F-111 was preferred.

Following the 1966 Defence White Paper, the Air Ministry

decided on two aircraft: the F-111K, with a longer-term replacement being a

joint Anglo-French project for a variable geometry strike aircraft – the Anglo

French Variable Geometry Aircraft (AFVG). A censure debate followed on 1 May

1967, in which Healey claimed the cost of the TSR-2 would have been £1,700

million over 15 years including running costs, compared with £1,000 million for

the F-111K/AFVG combination. Although 10 F-111Ks were ordered in April 1966

with an additional order for 40 in April 1967, the F-111 programme suffered

enormous cost escalation coupled with the devaluation of the pound, far

exceeding that of the TSR-2 projection. Many technical problems were still

unresolved before successful operational deployment and, faced with

poorer-than-projected performance estimates, the order for 50 F-111Ks for the

RAF was eventually cancelled in January 1968.

To provide a suitable alternative to the TSR-2, the RAF

settled on a combination of the F-4 Phantom II and the Blackburn Buccaneer,

some of which were transferred from the Royal Navy. These were the same

aircraft that the RAF had derided in order to get the TSR-2 go-ahead, but the

Buccaneer proved capable and remained in service until 1994. The RN and RAF

versions of the Phantom II were given the designation F-4K and F-4M

respectively, and entered service as the Phantom FG.1 (fighter/ground attack)

and Phantom FGR.2 (fighter/ground attack/reconnaissance), remaining in service

(in the air-to-air role) until 1992.

The RAF's Phantoms were replaced in the

strike/reconnaissance role by the SEPECAT Jaguar in the mid-1970s. In the

1980s, both the Jaguar and Buccaneer were eventually replaced in this role by

the variable-geometry Panavia Tornado, a much smaller design than either the

F-111 or the TSR-2. Experience in the design and development of the avionics,

particularly the terrain-following capabilities, were used on the later Tornado

programme. In the late 1970s, as the Tornado was nearing full production, an

aviation businessman, Christopher de Vere, initiated a highly speculative

feasibility study into resurrecting and updating the TSR-2 project. However,

despite persistent lobbying of the UK government of the time, his proposal was

not taken seriously and came to nothing.

Survivors

TSR-2 XR222 photographed at Duxford, 2009

TSR-2 XR220 at RAF Museum Cosford, UK

Forward fuselage used for testing seen on display at

Brooklands Museum

The TSR-2 tooling, jigs and many of the part completed

aircraft were all scrapped at Brooklands within six months of the cancellation.

Two airframes eventually survived: the complete XR220 at the RAF Museum,

Cosford, and the much less complete. XR222 at the Imperial War Museum Duxford. The

only airframe ever to fly, XR219, along with the completed XR221 and part

completed XR223 were taken to Shoeburyness and used as targets to test the

vulnerability of a modern airframe and systems to gunfire and shrapnel. Four

additional completed airframes, XR224, XR225, XR226 and one incomplete airframe

XR227 (X-06,07,08 and 09) were scrapped by R. J. Coley and Son, Hounslow

Middlesex. Four further airframe serials XR228 to XR231 were allocated but

these aircraft were allegedly not built. Construction of a further 10 aircraft

(X-10 to 19) allocated serials XS660 to 669 was started but all partly built

airframes were again scrapped by R. J. Coley. The last serial of that batch,

XS670 is listed as "cancelled", as are those of another batch of 50

projected aircraft, XS944 to 995. By coincidence, the projected batch of 46

General Dynamics F-111Ks (of which the first four were the trainer variant

TF-111K) were allocated RAF serials XV884-887 and 902–947,[124] but these again

were cancelled when the first two were still incomplete.

The haste with which the project was scrapped has been

the source of much argument and bitterness since and is comparable to the

cancellation and destruction of the American Northrop Flying Wing bombers in

1950,[125] and the Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow interceptor that was scrapped in

1959.