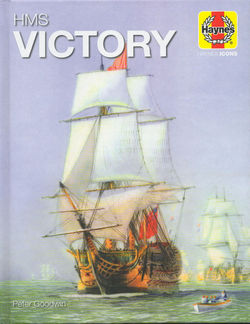

HAYNES

HMS VICTORY ROYAL NAVY HORATIO NELSON TRAFALGAR 1765-1812 FIRST RATE SHIP OF

THE LINE

AN INSIGHT INTO OWNING,

OPERATING AND MAINTAINING THE ROYAL NAVY�S OLDEST AND MOST FAMOUS WARSHIP

HARDBOUND BOOK in ENGLISH

The ships history / Career summary

Captains

Design

Layout / Structure

Decoration / Steering gear

Ground tackle / Pumps / Boats

Sheeting of the Hull / Crew

Accommodations

Masts and yards / Standing

rigging

Running rigging / sails

Guns

Sources for tables

The Photographs

The Drawings

Construction

Decoration

Layout

Accommodation and Steering

Ground tackle / Pumps

Armament / Shot

Mast and spars / Standing

Rigging

Running Rigging

The Sails / Boats

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Additional Information from

Internet Encyclopedia

HMS Victory is a 104-gun

first-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, ordered in 1758, laid down in

1759 and launched in 1765. She is best known for her role as Lord Nelson's

flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805.

She additionally served as

Keppel's flagship at Ushant, Howe's flagship at Cape Spartel and Jervis's

flagship at Cape St Vincent. After 1824, she was relegated to the role of

harbour ship.

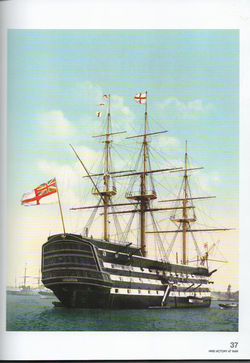

In 1922, she was moved to a dry

dock at Portsmouth, England, and preserved as a museum ship. She has been the

flagship of the First Sea Lord since October 2012 and is the world's oldest

naval ship still in commission, with 241 years' service as of 2019.

In December 1758, Pitt the

Elder, in his role as head of the British government, placed an order for the

building of 12 ships, including a first-rate ship that would become Victory.[2]

During the 18th century, Victory was one of ten first-rate ships to be

constructed. The outline plans were based on HMS Royal George which had been

launched at Woolwich Dockyard in 1756, and the naval architect chosen to design

the ship was Sir Thomas Slade who, at the time, was the Surveyor of the Navy.

She was designed to carry at least 100 guns. The commissioner of Chatham

Dockyard was instructed to prepare a dry dock for the construction. The keel

was laid on 23 July 1759 in the Old Single Dock (since renamed No. 2 Dock and

now Victory Dock), and a name, Victory, was chosen in October 1760. In 1759,

the Seven Years' War was going well for Britain; land victories had been won at

Quebec and Minden and naval battles had been won at Lagos and Quiberon Bay. It

was the Annus Mirabilis, or Year of Miracles (or Wonders), and the ship's name

may have been chosen to commemorate the victories or it may have been chosen simply

because out of the seven names shortlisted, Victory was the only one not in

use. There were some doubts whether this was a suitable name since the previous

Victory had been lost with all on board in 1744.

A team of 150 workmen were

assigned to construction of Victory's frame. Around 6,000 trees were used in

her construction, of which 90% were oak and the remainder elm, pine and fir,

together with a small quantity of lignum vitae. The wood of the hull was held

in place by six-foot copper bolts, supported by treenails for the smaller

fittings. Once the ship's frame had been built, it was normal to cover it up

and leave it for several months to allow the wood to dry out or

"season". The end of the Seven Years' War meant that Victory remained

in this condition for nearly three years, which helped her subsequent

longevity. Work restarted in autumn 1763 and she was floated on 7 May 1765,

having cost �63,176 and 3 shillings, the equivalent of �8.48 million

today.[Note 1]

On the day of the launch,

shipwright Hartly Larkin, designated "foreman afloat" for the event,

suddenly realised that the ship might not fit through the dock gates.

Measurements at first light confirmed his fears: the gates were at least 9�

inches too narrow. He told the news to his superior, master shipwright John

Allin, who considered abandoning the launch. Larkin asked for the assistance of

every available shipwright, and they hewed away enough wood from the gates with

their adzes for the ship to pass safely through. However, the launch itself

revealed significant problems in the ship's design, including a distinct list

to starboard and a tendency to sit heavily in the water such that her lower

deck gunports were only 4 ft 6 in (1.4 m) above the waterline. The first of

these problems was rectified after launch by increasing the ship's ballast to

settle her upright on the keel. The second problem, regarding the siting of the

lower gunports, could not be rectified. Instead it was noted in Victory's

sailing instructions that these gunports would have to remain closed and

unusable in rough weather. This had potential to limit Victory's firepower,

though in practice none of her subsequent actions would be fought in rough

seas.

Because there was no immediate

use for her, she was placed in ordinary and moored in the River Medway.

Internal fitting out continued over the next four years, and sea trials were

completed in 1769, after which she was returned to her Medway berth. She

remained there until France joined the American War of Independence in 1778. Victory

was now placed in active service as part of a general mobilisation against the

French threat. This included arming her with a full complement of smooth bore,

cast iron cannon. Her weaponry was intended to be thirty 42-pounders (19 kg) on

her lower deck, twenty-eight 24-pounder long guns (11 kg) on her middle deck,

and thirty 12-pounders (5 kg) on her upper deck, together with twelve

6-pounders on her quarterdeck and forecastle. In May 1778, the 42-pounders were

replaced by 32-pounders (15 kg), but the 42-pounders were reinstated in April

1779; however, there were insufficient 42-pounders available and these were

replaced with 32-pounder cannons instead.

Vice-Admiral Nelson hoisted his

flag in Victory on 18 May 1803, with Samuel Sutton as his flag captain. The

Dispatches and Letters of Vice Admiral Lord Nelson (Volume 5, page 68) record

that "Friday 20 May a.m. ... Nelson ... came on board. Saturday 21st

(i.e.the afternoon of the 20th) Unmoored ship and weighed. Made sail out of

Spithead ... when H.M.Ship Amphion joined, and proceeded to sea in company with

us" � Victory's Log. Victory was under orders to meet up with Cornwallis

off Brest, but after 24 hours of searching failed to find him. Nelson, anxious

to reach the Mediterranean without delay, decided to transfer to Amphion off

Ushant. The Dispatches and Letters (see above) record on page 71 "Tuesday

24 May (i.e. 23 May p.m.) Hove to at 7.40, Out Boats. The Admiral shifted his

flag to the Amphion. At 7.50 Lord Nelson came on board the Amphion and hoisted

his flag and made sail � Log."

On 28 May, Captain Sutton

captured the French Ambuscade of 32 guns, bound for Rochefort. Victory rejoined

Lord Nelson off Toulon, where on 31 July, Captain Sutton exchanged commands

with the captain of Amphion, Thomas Masterman Hardy and Nelson raised his flag

in Victory once more.

Victory was passing the island

of Toro, near Majorca, on 4 April 1805, when HMS Phoebe brought the news that

the French fleet under Pierre-Charles Villeneuve had escaped from Toulon. While

Nelson made for Sicily to see if the French were heading for Egypt, Villeneuve

was entering C�diz to link up with the Spanish fleet. On 9 May, Nelson received

news from HMS Orpheus that Villeneuve had left Cadiz a month earlier. The

British fleet completed their stores in Lagos Bay, Portugal and, on 11 May,

sailed westward with ten ships and three frigates in pursuit of the combined

Franco-Spanish fleet of 17 ships. They arrived in the West Indies to find that

the enemy was sailing back to Europe, where Napoleon Bonaparte was waiting for

them with his invasion forces at Boulogne.

The Franco-Spanish fleet was

involved in the indecisive Battle of Cape Finisterre in fog off Ferrol with

Admiral Sir Robert Calder's squadron on 22 July, before taking refuge in Vigo and

Ferrol. Calder on 14 August and Nelson on 15 August joined Admiral Cornwallis's

Channel Fleet off Ushant. Nelson continued on to England in Victory, leaving

his Mediterranean fleet with Cornwallis who detached twenty of his thirty-three

ships of the line and sent them under Calder to find the combined fleet at

Ferrol. On 19 August came the worrying news that the enemy had sailed from

there, followed by relief when they arrived in C�diz two days later. On the

evening of Saturday, 28 September, Lord Nelson joined Lord Collingwood's fleet

off C�diz, quietly, so that his presence would not be known.

After learning he was to be

removed from command, Villeneuve put to sea on the morning of 19 October and

when the last ship had left port, around noon the following day, he set sail

for the Mediterranean. The British frigates, which had been sent to keep track

of the enemy fleet throughout the night, were spotted at around 1900 hours and

the order was given to form line of battle. On the morning of 21 October, the main

British fleet, which was out of sight and sailing parallel some 10 miles away,

turned to intercept. Nelson had already made his plans: to break the enemy line

some two or three ships ahead of their commander-in-chief in the centre and

achieve victory before the van could come to their aid. At 0600 hours, Nelson

ordered his fleet into two columns. Fitful winds made it a slow business, and

for more than six hours, the two columns of British ships slowly approached the

French line before Royal Sovereign, leading the lee column, was able to open

fire on Fougueux. Around 30 minutes later, Victory broke the line between

Bucentaure and Redoutable firing a treble shotted broadside into the stern of

the former from a range of a few yards. At a quarter past one, Nelson was shot,

the fatal musket ball entering his left shoulder and lodging in his spine. He

died at half past four. Such killing had taken place on Victory's quarter deck

that Redoutable attempted to board her, but they were thwarted by the arrival

of Eliab Harvey in the 98-gun HMS Temeraire, whose broadside devastated the

French ship. Nelson's last order was for the fleet to anchor, but this was

countermanded by Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood. Victory suffered 57 killed

and 102 wounded.

Victory had been badly damaged

in the battle and was not able to move under her own sail. HMS Neptune

therefore towed her to Gibraltar for repairs. Victory then carried Nelson's

body to England, where, after lying in state at Greenwich, he was buried in St.

Paul's Cathedral on 9 January 1806.